Harriet Tubman | From the Railroad to A Spy

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Journey through the events and details of her incredible life story that are seldom told.

Harriet Tubman | From the Railroad to a Spy is an epic documentary that tells her complete story. Journey through the events and details of her incredible life story that are seldom told; from the underground railroad, to her work as a Union Army scout and spy in military campaigns from South Carolina to Florida.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

SCETV Specials is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

Harriet Tubman | From the Railroad to A Spy

Special | 56m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Harriet Tubman | From the Railroad to a Spy is an epic documentary that tells her complete story. Journey through the events and details of her incredible life story that are seldom told; from the underground railroad, to her work as a Union Army scout and spy in military campaigns from South Carolina to Florida.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch SCETV Specials

SCETV Specials is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More from This Collection

Find independent producers who have submitted programs to South Carolina ETV.

Breakfast in Beaufort: Journeys Through Time

Video has Closed Captions

A group of wise men, ranging in age from 84 to 101, gather weekly for coffee and breakfast. (26m 45s)

Video has Closed Captions

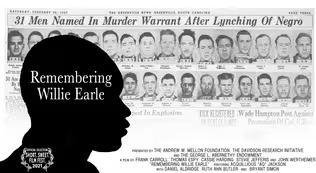

On February 17, 1947, 24-year-old Willie Earle was brutally killed in South Carolina. (17m 13s)

Selections from Handel’s Messiah

Video has Closed Captions

Handel's Messiah performed by the Bob Jones University symphony and choirs. (58m 4s)

Video has Closed Captions

TOUCHING THE SOUND traces the artistic development of young pianist Nobuyuki Tsujii. (56m 46s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ Harriet Tubman is one of the most under-recognized people in American history, based on her accomplishments.

Known as a women's rights activist, humanitarian, and women's rights champion, however, throughout her life, she assumed several daring and incredible roles.

Most people know her as one of the most famous conductors on the Underground Railroad.

But what most people don't know is that she was also a nurse, Army spy and scout who was involved in one of the most important raids in the civil war.

And on top of everything else that she did for the government and our country to support herself, she had to sell baked goods, and knowing how well she did, with everything that she did, she probably baked a mean pie as well.

♪ Most of her life, Harriet spent in the North.

Yet it's her time and most importantly, her work in the Low Country of South Carolina and especially on Hilton Head Island that really deserves recognition.

Named Araminta Ross at birth when she was a slave, she was called Minty by her family, Grandma Moses, by those that she rescued and General by John Jones and some of the military officers that she encountered.

She chose to be called Harriet Tubman as her freedom name when she married John Tubman.

Regardless of what she was called, she was small in stature, yet filled with incredible courage and convictions.

Standing at only five foot two, Harriet was a giant in all that she accomplished, put to work as a slave as early as five years old, she was hired out by her owner to care for an infant.

Throughout her life as a slave, usually as an additional form of punishment for what was considered rude and disrespectful behavior, Harriet was given hard labor that was mostly given to men, like hauling logs and working with mule teams.

In addition to the labor, she experienced excessive cruelty from lashings as well as a life threatening concussion.

♪ The intense level of cruelty that she experienced forced her to plan her escape.

Although the concussion caused her debilitating headaches and unexpected sleeping spells that continued throughout her life.

After several years from suffering from headaches, the constant pain eventually led her to have brain surgery at Boston, Massachusetts General Hospital.

Prior to the surgery, when she was offered anesthesia she refused, insisting that she'd be able to chew on a bullet instead.

♪ It has been said that she chose to depend on her incredible grit as well as memories of the amputated soldiers that she nursed during the war who also refused to accept anesthesia.

It was that kind of strength and determination that enabled Harriet to make 13 trips south and free 70 enslaved relatives and strangers.

On her last trip south, She rescued her aging parents.

Her successful rescues came from her ability to outwit her pursuers by using disguises and evasive tactics, resulting in her never losing one of her passengers on their road to freedom.

Harriet's success at avoiding capture was attributed to her brilliance, skilled in clandestine tactics, distractions and changing her appearance, even when in the line of sight of bounty hunters, she figured out ways of evading them on the fly.

Driven and fearless, she was known for carrying a gun during her escapes, making several trips north, even though she had upwards of a $40,000 bounty on her head.

Unable to understand the wanted posters, she was still successful, leading them to freedom, because she executed her raids only on weekends to avoid the runaway information that was being spread by the newspapers, as well as only going during the winter months when less people were traveling.

Navigating through the woods at night and through thick underbrush was extremely difficult.

However, Harriet was taught how to survive by living off the land by her father and grandmother and her enslavement labor of walking into wet marshes to check on muskrat traps taught her how to be comfortable in outdoors and recognizing nature's different sounds.

Trip after trip, she learned to improvise and become very handy, able to utilize what she could find.

Her knowledge of the region and its wildlife were elements that she would often use to her advantage.

Several bodies of water were between enslavement and freedom, which meant that crossing rivers and creeks successfully required understanding depths and tides, as well as helped her wash off the scent of her passengers.

Knowing that moss only grows on trees facing the North enabled her to feel what direction she needed to take in the darkness.

Mimicking different bird sounds, especially owl calls to signal passengers helped them to avoid suspicion.

Tubman could identify the Big Dipper and the North Star, which guided her all the way to Canada.

♪ Harriet was responsible for feeding and finding ways to heal her passengers.

Winter travel might have made foraging difficult, but she was quite proficient at keeping them fed.

Her ability to forage and identify a wide variety of edible nuts, such as acorn and pinion, provided necessary proteins while sap and conifer leaves, thistle shoots or burdock roots were plants that could be consumed raw.

She became highly skilled as a herbalist, carrying herbs with her for pain relief and to clean wounds.

Being on the run, especially under the cover of darkness, brought additional challenges as well as accidents.

In the event of an injury.

She used Craneskill and lily roots to heal wounds and river herbs for intestinal issues.

Traveling long distance with children brought in challenges.

In addition to slowing them down, keeping them still or silent was especially difficult.

On a few of her trips when she escorted very small children, in order for them to be kept quiet, she would feed them bread laced with valerian root to calm them down or opium to put them to sleep.

Strong allies against slavery.

Harriet Tubman and John Brown supported and respected each other, believing that violence was the only way for it to be abolished.

Introduced in Canada while planning his infamous raid on the U.S. arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, Tubman shared her valuable abolitionist connections and extensive contacts to helping raise funds to support his work.

Tapping into her network of freed slaves who successfully made it to Canada, she recruited volunteers for Brown.

Tubman helped to plan the raid with her intimate knowledge of trails and escape routes becoming an important role in their strategy.

The raid contributed to regional tensions and was designed to spark widespread slave rebellions in southern states.

Brown hoped that the raid would allow him to amass an army of free and emancipated slaves to join the fight to end slavery.

Originally planning to participate, Tubman became ill, unable to join him.

In the end, the raid on Harpers Ferry failed.

With only 22 men participating, the small group was quickly surrounded and suppressed by U.S. Marines.

John Brown was tried, found guilty and hung.

Although the raid was unsuccessful, many believe that it added to the social and political tensions that led to the Civil War.

Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry was viewed as the work of a fanatic.

Considered by Tubman and others as a martyr, he became an icon for the Union, with his name being made into a song that eventually became the rallying cry for Union troops.

Having lost a friend, Tubman mourned his death, later saying, he done more in dying than 100 men would in living.

When you think about Harriet Tubman, she was one of the biggest risk takers.

She was willing again and again and again and again to risk her life, to risk her safety, to risk her very own freedom, to free other people.

She did it on the Underground Railroad and freed scores of friends and family and community members, and then she came to South Carolina to the belly of the beast.

♪ music fades ♪ To set the stage, months into the Civil War, as Lincoln, and his cabinet formulated their war plans, they were in search of a strategic port of operations.

In order to become more efficient in launching their missions, the Union Army needed to establish a southern stronghold to fight the Confederates as well as find ways to disrupt their military equipment and food supply routes.

The Port Royal Sound Area, which includes Hilton Head Island, was a strategic location due to its navigable waterways and Deep Harbor that's situated between the key Confederate cities of Charleston, Beaufort and Savannah.

The area was perfect to establish the Union headquarters of the South, which was responsible for operations in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

Hilton Head's Harbor was also very conducive to enabling the Union to build, repair and resupply their naval ships.

Even though the Confederates had established forts on Hilton Head Island, as soon as the Navy pulled into the harbor, the soldiers abandoned the area with most of the plantation owners fleeing behind them, leaving thousands of enslaved Gullah people behind.

♪ The enslaved that lived on the coastal sea islands were unique, because they were Gullah descendants who blended their West African traditions into a unique culture and language with the Union establishing military bases on the island, the Gullah, along with 10,000 freedom seeking slaves called contrabands, were eager to learn and experience their newfound citizenship in addition to joining the war effort.

♪ With so many formerly enslaved to care for and educate, several Northern charities and organizations began sending teachers to the area to help provide the skills necessary for the Gullah to become educated and self-sufficient.

Among the abolitionists who sent representatives down to the sea island, Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts sent Harriet Tubman in May of 1862 to teach and assist with the formerly enslaved and eventually nurse, ill and wounded soldiers.

By the time Harriet arrived in Beaufort, she had already made a name for herself as a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

Her work and opinion was very influential, enabling her to establish a significant stature and recognition within prominent circles, the military and the government.

Harriet's level of importance, especially as a Black woman during those times, was unprecedented.

Her value to the Union Army was clearly expressed when General David Hunter said, Pass the bearer, Harriet Tubman, to Beaufort, and back to this place and wherever she wishes to go and give her passage at all times on all government transport.

Harriet is a valuable woman.

As the war progressed, Harriet spent a significant amount of time tending to injured soldiers whose numbers seemed never ending.

Day after day, the wounded would come in and Harriet described each day in vivid detail.

<Tubman re-enactment> Every morning I would, I'd go over and I'd get a hunk of ice and I'd get a basin and put some water in it with a sponge, and I'd gone over to the hospital.

Now, by the time I'd bathed four or five of them, the heat... would melt the ice.

And then when you looked in the basin, the basin looked like clear blood.

>> Harriet's value to the Union Army included her success on the Underground Railroad, which was found in part, because as a fugitive slave herself, she was able to easily blend into various environments, often altering her appearance and establishing trust with the slaves.

With an incredible memory for details, she could scout out escape routes throughout the South, which she shared with the military, who eventually realized that she could provide them with invaluable intelligence and give them significant advantages in the war effort.

Even though she spent three years in Beaufort and Hilton Head Island, she was still at a disadvantage because the enslaved people spoke Gullah, a Creole based language that's a combination of English and West African words.

Of course, most of the enslaved didn't trust the soldiers or their intentions.

However, she used her ability to blend in to gain the trust of successful escaped slaves.

With the help of several scouts called Black Dispatches, who risked their lives reentering Confederate territory to gather information and spy on plantation owners, she was able to collect valuable intelligence.

The incredibly detailed intelligence that she was able to amass with the assistance of several of her scouts regarding the surrounding area, proved that she was a very valuable asset to the Union officers.

One of the Union's goals for establishing a base of operations where they did was to execute a series of river raids during the spring and summer of 1863 to deny the South access to its critical food supplies of rice, cotton and grain around the region.

The most logical way to do that was, to devise plans that would not only cause enough chaos to disrupt and punish plantation operations, but also liberate the enslaved.

The thinking was that since the Union needed reinforcements, the liberated slaves could also join their ranks, thus bolstering their numbers.

Union Colonel James Montgomery, and abolitionist and jayhawker came to Hilton Head Island and was chosen to lead several of the missions that were pivotal to crippling the South.

After recruitment efforts in Key West, Montgomery was eager to add soldiers to his command, appreciating the loyalty and dedication of the colored troops.

<David Schafer> James Montgomery is a really fascinating, militant abolitionist.

He was a friend of John Brown, so that kind of puts you in a category right there, So basically, the escalation of violence.

Montgomery became just more and more strident, I guess you would say, both admired and despised, depending on your perspective.

Montgomery, really stepped up his kind of anti-slavery agitation at that point.

And most notably, Montgomery and his followers were very active in the Underground Railroad.

So there was a lot of violence pre-Civil War, and then finally, when the war broke out, Montgomery, ended up commanding the third Kansas Regiment.

Montgomery took it to the next level when he got to the Department of the South and South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, a very harsh war to punish southern slave holders, and two to free enslaved people.

So he's really a dynamic figure.

He took that war and slavery to the Department of the South.

The fundamental thing, though, that he maintained really a passion to end slavery.

He just thought it, like John Brown, slavery had to go.

It was an essential step to get to where we needed to go, and he never lost that drive.

♪ music ♪ Located in the Low country of South Carolina, just north of Beaufort, the Combahee River runs 50 miles into the state and was essentially a river highway that connected several large rice and cotton plantations to area mills.

The scenic marshlands that can be seen today were once an organized network of rice fields and canals.

Rice was a very lucrative crop for the Low country, requiring hundreds of slaves to work the fields, generating incredible wealth for the state's most affluent landowners.

Records state that by 1850, nearly 6% of South Carolina's rice crop was produced along the Combahee.

One plantation owner, Henry Middleton, had a total of 523 slaves, who produced over 2.8 million of rice, which would be equivalent to $2.5 million today.

Because of the amount of wealth that rice generated, for abolitionists, it was a symbol of oppression and a clear path to financially devastating the South.

In addition to the significant financial impact and importance that the Combahee had, it was also key militarily.

Along the river, several Confederate camps were also situated, making the area key to the South's delivery system.

The Combahee River raid, the strategy and decision to execute it, ultimately made it one of the most important raids during the Civil War.

<David> The Combahee River raid to me was just one of the most compelling, fascinating intriguing events of the war that it is hardly remembered today.

It was a remarkable raid.

James Montgomery led it as a commander of three U.S. Navy steamboats.

Harriet Tubman's collaboration was vital to its success.

At 2:30 a.m. on June 1st, which was a moonless night, a small flotilla of three ships, the John Adams, The Sentinel and the Harriet A. Weed snaked their way towards the Combahee River.

The plan was to land at Fields Point, Tar Bluff and the Combahee Ferry and seize food and supplies, as well as burn the plantation buildings and rice fields.

However, one of the ships, the Sentinel, ran aground, delaying the mission and forcing the men and materials to be transferred to the other ships.

Once the soldiers were able to regroup, the John Adams and the Harriet A. Weed split up along the river to conduct separate raids.

Montgomery led the expedition on the lead vessel, the John Adams, accompanied by Harriet Tubman and two of her scouts, Charles Simmons and Samuel Heyward, who were very familiar with the area.

They were joined by about 300 men from the third Rhode Island heavy artillery, which included 150 soldiers from the U.S. colored troops, 2nd South Carolina volunteers, an all-Black unit.

The raid was an especially dangerous one as the river had significant expanses of marsh along its banks, leaving the gunboats completely exposed At every landing, the troops would disembark, engage with the Confederates and hold the area.

As they advanced up the river, the Confederates were confused, unprepared and limited in their ability to counterattack as some of the plantations were up to two miles away from the river.

Surrounding the river were the Blake, Middleton Heyward and Loden plantations.

Thomas Heyward, by the way, was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

The Heyward and Loden plantations combined owned close to 700 slaves.

Plantation after plantation, the houses were burned and the Union forces flooded the rice fields and burned tremendous stores of rice.

The sight of gunboats was an incredible and unexpected sight to the enslaved.

When they saw ships with Black Union soldiers on board, they ran towards them as their overseers helplessly demanded that they stay.

Some unsure about what was happening, ran into the woods in fear.

The efforts towards freedom, along with chaos and confusion with hundreds of slaves, came running from as far away as eight miles inland In a desperate attempt to keep the enslaved from escaping, rebels and overseers tried to chase down the slaves, screaming and firing their guns.

Once one of the plantation owners realized what was happening, he asked several of his male slaves to assist him in keeping his slaves from running and protecting his property from being damaged.

Surprisingly, they ran away with the other slaves.

After the ships completed their missions, and the slaves heard the sounds of the steam whistle, word quickly spread that Lincoln's boats came to set them free.

From every house, road or across the field, they came running.

Hundreds upon hundreds of men, women and children suddenly crowded the river's banks, wading through the water, trying to reach the ships.

The sheer numbers of people pouring onto what they called Lincoln's gunboats weighed them down, overwhelming them so much that they couldn't even leave the shore.

♪ Tubman, later describing what she saw during the raid, said that once the signal from the ship was given, she saw slaves running everywhere, women carrying everything that you could think of.

<Harriet re-enactment> I've never seen such a thing in all my time.

Oh, we laughed and we laughed and we laughed.

There was a woman coming cross with a pail on her head, rice steaming out of it like it had just come off the fire.

Had some young'uns hanging around the bottom of her, had one young'un hanging on the back of her neck, holding on to her forehead, eating out of that pot with all he might.

And then she had a bag on her back with a pig in it.

Well, I look over, I see another woman coming.

She got a bag on her back, a basket on her head, but she got two pigs, two pigs in the back, three children hanging round her skirt tail I say, Oh, well, now here she come with the pig, two pigs on the back.

One was white and one was black.

So we named the white one, Beauregard, and we named the black one, Jeff Davis.

Then she went on down.

Now, here it is.

I see some more women coming up.

They got twins.

Twins hanging off the back, Off the shoulder gathered round.

Got pigs hanging off of them.

Now we got the pigs squealing, the children screaming and the chickens squawking, but then it reminded me.

It was like when they came out of Israel coming into Egypt.

<David> Yeah.

Tubman has these great descriptions she provided to Sarah Bradford later of just the jubilation in the air, once that Combahee Ferry site where they docked the John Adams, and Captain William Althorp talks about that.

The most striking portion of the whole affair, he wrote, was the reaction of the people.

They were just so grateful, so excited.

So we've been praying for this day.

God bless you.

And there were tears flowing down their cheeks that finally the day of liberation had arrived.

So it's like something out of a movie, I guess.

These people, all of a sudden, these steamboats of freedom, showed up kind of out of nowhere, although I think they had an inkling it was coming.

In fact, Joshua Nichols, the plantation owner at Long Brow, talks about that the enslaved people in this plantation were talking with some of the soldiers who were probably from the other nearby plantations, like, hey, how you doing there?

>> As the escapees ran towards the ships that were just offshore, U.S. colored troops awaited in rowboats to transport them to the ships, but as you can imagine, pure chaos ensued in the process.

(screaming from a crowd) Tubman, who didn't speak nor understand the Low country Gullah dialect, ran to the ship's deck and began to sing a popular spiritual song used by abolitionists that not only established their trust, but helped calm the group down.

Tubman later said that her only regret was wearing a green dress that became torn by the excited and grateful freedmen boarding the ships.

(acapella singing) Wade in the water.

Wade in the water.

Children.

Wade in the water.

Oh, God's gonna trouble the water.

Overall, the expedition was an incredible success.

The Union was able to take whatever food and supplies that they could, as well as burn down the Combahee Ferry Bridge and destroy vital rice fields.

If it wasn't for the third ship running aground, the number of liberated would have been higher.

The mission ended without any Union troop casualties, except for one contraband and a Confederate soldier.

Union Captain Althrop of the U.S.

Colored Troops 34th Company B described the excitement of the suddenly freed slaves.

♪ They rushed toward us, running over with delight and overwhelmed us with blessings.

Lord help you, massa, they would cry often with tears running down their dark cheeks and clinging to our hands, knees, clothing and weapons.

The Lord bless you.

We have been expecting and praying for you this long time.

Oh, massa Thank.

the Lord, you come at last.

Following the expedition.

It's interesting to see how the raid was depicted in the newspaper, depending on what side of the war they supported.

A pro-Union newspaper called the Commonwealth reported on July 10th.

Colonel Montgomery and his gallant band of 300 Black soldiers, under the guidance of a Black woman, dashed into the enemy's country, struck a bold and effective blow, destroying millions of dollars worth of property.

The raid striking terror into the hearts of rebeldom, brought off nearly 800 slaves and thousands of dollars worth of property without losing a man or receiving a scratch.

It was a glorious consummation.

In contrast, the pro southern newspaper Charleston Mercury reported a destructive Yankee raid along the banks of the Combahee.

After pillaging the premises of these gentlemen, the enemy set fire to the residences, outbuildings and whatever grain, etc.

they could find, and after their work of devastation, there had been consummated, they destroyed the pontoon bridge at Combahee Ferry.

They then drew off, taking with them between 600 and 800 hundred Negroes belonging chiefly, as we are informed to Mr. Heyward and Mr. Lodens.

Beside his residence and outbuildings which were burned, he lost a choice library of rare books valued at $10,000.

♪ Several overseers are missing, and it is supposed that they are in the hands of the enemy.

Although the accounts are biased, both accounts have elements of truth to them.

Regardless of the version, the success of the raid still remains, and several hundreds of enslaved people were freed.

<David> Now, Joshua Nichols, who was the owner of the Longbrow Plantation, he submitted for claims with the Confederate government afterwards for reimbursement, and he documented 73 enslaved people who the Yankee steamboats whisked to freedom, and they all left.

The only one who stayed behind was and sadly an older, bedridden woman who died shortly after.

So everybody else got on the boat and left.

And he was shocked.

He was just mortified that, as he put it, that none were loyal to the rebel.

He was in shock, so it was like, to me amazing disconnect.

He thought that they were content and, you know, providing for them.

And, you know, how dare they leave?

He and William C Heyward are two of the White planters who left behind some some written documentation.

John Nichols wrote letters to the Charleston Mercury, but yeah, he was just flabbergasted.

He has a great description, actually, where when he's informed that these two Yankee boats are showing up on the river, you know, he told his overseer to round up the slaves and they wouldn't come to him, so he went to their quarters and he said, let's go hide in the woods, you know.

And they said, he said, they all nodded their head and acted like they would, but none of them went with him, and then finally he had to go run and hide and watch in stunned silence as the, you know, the Yankees started burning down his house and his library and all these other outbuildings.

>> Colonel James Montgomery, commander of the regiment, later noted Harriet Tubman as a most remarkable woman and invaluable as a scout.

<David> Harriet Tubman was indispensable to the raid.

She collaborated with Colonel James Montgomery and other White officers in amassing the intelligence about what they would find on the Combahee River on those plantations where they were located.

And she was the really essential go-between, between the officers planning and carrying out the raid and the people who had escaped enslavement there.

Including men who identified locations of torpedoes, and though there were people familiar with the Combahee River on all of the steamboats.

So I really view her as a real trailblazer.

Never before had a woman, much less a woman of color played such a large, indispensable role in carrying out a U.S. military expedition.

Now, Harriet Tubman did not lead the expedition.

That was actually James Montgomery.

In fact, in the Boston Commonwealth in one newspaper she talks about expedition was carried out under the lead of the brave Colonel Montgomery, as she put it.

Although she did also say that, you know, shouldn't we colored people get some credit for that exploit as well?

So, she certainly had a huge role in it, but the way the military was set up, you know, Montgomery was a military commander.

And, you know, he the responsibility fell on his shoulders.

>> Several affidavits filed after the raid by plantation owners listed all of the property that was lost, including the slaves who were described as captured property.

<David> And we think that it was probably the largest single emancipation event of the Civil War, the single largest.

There are different numbers, but somewhere between 700 and 800 people crammed on to those two steamboats with the Navy personnel and the White and Black soldiers and got to freedom in Beaufort, and then for some of them subsequently joined the military right after that.

The newly freed men, self named the Combahees were moved to Montgomery Hill, a village in Port Royal, South Carolina, where they were provided with houses and a fresh start.

Out of the 756 who were liberated by the exposition, Dr. Fields Black, in her book, has identified 180 descendants of the raid.

Among the liberated, 150 were immediately enlisted into Union service to fight for their freedom, as well as those who were left behind.

<Dr.

Fields Black> It's fascinating to me to think about the reasons why not everyone got on the boat and what happened to the people who got left behind, who eventually did get to Beaufort, and probably got there pretty quickly?

So there was the man who was enslaved as a hunter.

He was a deer hunter.

The slave holder joined the Confederate Army and took him in service to where they were encamped, and he said that they were encamped about a day away.

And he came back once a week to visit his family.

He came back one week, they were there.

He came back the next week they were gone.

And if we think about another good example, where the soldiers from the first South Carolina and the second South Carolina.

Right!

Men who, many of them were freed, well, the men from the company were free for a day and boom, they're in the military.

You know, there's an elder who was freed on the Combahee who was in the rice fields when the gunboats pulled up and says they took the men out of the rice fields.

They took the hose out of their hands and they put a musket in it, and they sent them off to fight for the freedom of others.

They knew freedom wasn't free.

>> The sudden influx of new recruits gave the Union a tremendous boost to its ranks and proved to a doubtful nation that the US colored troops were not only capable, but loyal and dedicated fighters who were willing to risk their lives for freedom.

<David> And when Montgomery got back to Beaufort, he enlisted around 150 men who had been freed, men of military age.

So again, that kind of good and bad side of Montgomery, he didn't give those freed people of military age any choice.

They were marched to camp, put under guard there, issued uniforms, and they got back to Beaufort the morning of June 3rd.

And then basically within eight days after that, companies G and H were formed.

So a big part of the raid from Montgomery's perspective, was to get recruits for his regiment.

He had a long ways to go to fill out his regiment and needed recruits.

And on June 10th, it actually became official.

Regiment had 509 officers and men on June 9th, but on June 10th, 663 officers within eight days.

Men went from basically slave to soldier.

>> The raid also ushered in a new type of warfare by sneak attack or guerrilla tactics, which was unexpected and caused a significant blow to the struggling south who went without needed supplies, and most plantation owners went bankrupt.

♪ The Combahee raid was one of the first signs indicating the end of Southern strength and way of life.

The magnitude of the victory added to the strategy of using the sneak attack or guerrilla tactics used during the raid was so successful that Union forces adopted the style for future operations.

<David> In the war as soon as possible, actually, fewer people will die, if we can end the war sooner, and you do that by targeting everything.

You know, you capture property, encourage enslaved people to come to our side basically, destroy crops in the field, destroy their farms, destroy their ability to make munitions and weapons and all that.

And Montgomery would agree with it completely.

And when I discovered that, it really, to me, encapsulated what they were thinking.

And, you know, he was - Althorp has this thing about the people in the north are like, Oh, the shameful raids that they're carrying out, how terrible it is.

And he's like, No, this has to be done.

If you don't understand, you know, this is not a boxing match, or, you know, we don't want to just face the Confederates on the field of battle where, you know, the enemy is strongest.

We need to attack them in every way possible to hasten the end of the war.

♪ music ♪ >> Two days after the raid, in the early hours of the morning, Major General David Hunter, the commander of the Department of the South, ordered 1000 troops to burn down the town of Bluffton, which is just across the water from Hilton Head because it was a Confederate stronghold and hotbed for the secessionist movement.

The burning of Bluffton, which was richly detailed in a letter, which a rat, who didn't care about its historic significance, took a great bite out of it.

The greatly detailed letter describes how 238 Confederate soldiers were no match against the Union's significant military forces' destruction by burning down 75% of the town.

<David> James Montgomery really viewed the war as a war to end slavery, kind of by almost any means necessary.

And he really wanted the Southerners, the White southerners to feel that it really was a real war, that by using enslaved labor, that their wealth was through ill gotten means.

Various officers who observed Montgomery called it the use of fire and sword.

(laughs) So wielding fire and sword was a way to end the war sooner, especially after Ulysses S Grant took command early, was an emphasis on destroying the Southern capacity to wage war.

So that meant, destroying factories, burning crops in the field, you know, any way to keep munitions, supplies, food reaching the Confederate armies was really paramount to victory.

He viewed, this was a brutal war to end a brutal institution, the institution of slavery.

♪ music ♪ >> Weeks later, in an effort to disrupt the Confederate's food and supply lines, Montgomery led the U.S.

Colored Troops soldiers 2nd South Carolina, along with Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts in their first real combat campaign to Darien, Georgia, which was an important shipping point for cotton, rice and lumber.

The town which was undefended and without Confederate support, was looted and left in smoldering ruins.

The flames from the town were so incredible that they were seen as far as 15 miles away.

Only two buildings within the town survived.

The raid, which was depicted in the movie Glory, showed how at the time, the destruction of the town was a controversial act.

So burning Darien as it was basically vacated where maybe a few Southern guerillas using it, maybe blockade runners, there weren't enslaved people to free like on the Combahee River, but he made the decision that I shall burn this town.

That's basically what he told Robert Gold Shaw.

And I think it was more of the retribution.

I think he just felt that this was, you know, he wanted to deny the use of Darien for the rebels in any capacity, and it was just really a harbinger for the way that the war was evolving.

♪ music ♪ After the expeditions in South Carolina and Georgia, Colonel Montgomery, Colonel Higginson, along with U.S.

Colored Troop soldiers from the first South Carolina and the 33rd regiments as they moved further south into Jacksonville in an effort to force the Confederates to return their troops to the area and defend the coastline.

Harriet Tubman, who had special permission to continue with the troops, accompanied them into Florida, providing valuable intelligence to the Union, which enabled them to take Jacksonville without firing a single shot.

♪ music ♪ Regardless of Harriet's valuable military influence, and as the first woman of color in the United States history to scout out, plan and participate in a successful military raid, however incredibly, she was not paid for or fully recognized for her service.

During the war in order to supplement her income, the generals gave her permission to run an eating house in Beaufort, South Carolina, where at night she made and sold baked goods, gingerbread and root beer to the soldiers to support herself, as well as send money home to Auburn, New York.

<David> Harriet Tubman.

In fact, one of the officers said that she could get more information from them, than anybody.

So, she really was that key piece, I think, that made the raid possible where she would get the information and be the go between, between freed people and the White military commanders, so Tubman was an indispensable collaborator in that, you know, the fugitives who escaped the Union lines had that intelligence and were eager to share it, particularly with Harriet Tubman, there at Beaufort, South Carolina.

and Hilton Head, that area.

>> Incredibly for 34 years after the war ended, she submitted petitions for civil war pension in which she claimed that she was owed a total of $966 for her services as a nurse, spy and cook.

Her military service, however, was not well documented, and it is believed that the omission was to hide her identity and to protect her in the event of her capture from the Confederate Army.

<David> James Montgomery never wrote a report about the Combahee River raid, and I wish he would have and if he would have mentioned Tubman or not.

Montgomery was requested by General David Hunter to submit by telegraph what happened during the raid.

So Montgomery might not have written anything, but he wrote a brief paragraph was all he wrote about the raid.

He described taking the steamboats up and there were some sharp skirmishes and we destroyed all these things, freed, I think he's I think he said 725 people and took some fine horses, as he put it.

That's all he wrote about it.

He never wrote further.

In fact, I found other records where the Department of South, the headquarters in Hilton Head, they would constantly or frequently request that Montgomery send in his regiment reports and then brigade reports.

and Montgomery became a brigade commander of two or three Black regiments.

So he wasn't a stickler for the details of administration.

Montgomery was kind of in the John Brown mold of like, let's go do this, go do great damage.

Free enslaved people.

>> Ultimately, the gross omission in documentation was a great disservice to her.

And she only received $200 for three years of military service, even with influential friends, along with their support, only when her second husband died was she able to get a widow's pension of $8 a month.

By the time Harriet received any money, she was living in poverty and was being supported by her neighbors.

Eventually, she donated her home to a local church so that it could be used to care for aged and indigent colored people.

Her only request was that she too could live there for the rest of her days.

Prior to the release of Tubman's biography, Moses of her People in 1868, Tubman wrote a letter to her friend and fellow abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who was also formerly enslaved, yet rose to political prominence as a renowned public speaker and published writer.

In her letter, she asked him to endorse her book.

Douglass replied to Tubman with this letter, <Douglas> Dear Harriet, I'm glad to know that the story of your eventful life has been written by a kind lady, and that the same is soon to be published.

You ask for what you do not need when you call upon me for a word of commendation.

I need such words from you far more than you can need them from me, especially where your superior labors and devotion to the cause of the lately enslaved of our land are known as I know them.

The difference between us is very marked.

Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way.

You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way.

I have wrought in the day, you in the night.

I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes with being approved by the multitude.

While the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scared and foot sore bondmen and women who you have led out of the house of bondage and whose heartfelt, God bless you, has been your only reward.

The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism.

Excepting John Brown, of sacred memory.

I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people than you have.

Much that you have done would seem improbable to those who do not know you as I know you.

It is to me a great pleasure and a great privilege to bear testimony for your character and your works, and to say to those to whom you may come that I regard you in every way truthful and trustworthy.

Your friend, Frederick Douglass.

>> Prior to her death, Harriet Tubman was awarded full military honors.

Unfortunately, her work like that of most Black historical figures and their achievements in documented history as well as textbooks, gloss over what she had accomplished or only includes minor information, such as in her case with the Underground Railroad.

<David> Her help was essential to the success of the raid, but it was James Montgomery who was the military commander, who ordered different companies off at Tar Bluff and Fields Point and oversaw and made the decisions, but she was right there with him, from what I can gather.

She made it possible, but was not leading it like a general on the battlefield, so to speak.

She was more like the guide or pilot, so I think that was really her role to gather that intelligence and was right there shoulder to shoulder with Montgomery during the raid.

So I really hate that there's kind of a controversy that's developed.

Let's give her credit for that.

That's pretty amazing.

Yeah.

♪ music ♪ >> 2021 marks the 158 years since the Combahee River raid.

Time has clearly erased the philosophical differences that existed since the South challenged the North.

The differences, however, made the Civil War into one of the most pivotal points in American history.

It reunited and changed the direction of a divided nation.

It also forged the path into a future for nearly 3.9 million new citizens.

<David> But like with the Combahee River Raid, this is such an important, compelling story that we need to get these stories out there.

It's a marker of where we've been as a country and where we can go.

You see, kind of glimpses or hopes from you know, people back then collaborating to end this horrible institution of slavery, that it could be a reference point for how we move forward, and it's just a mixture, mixture of the hopes and dreams, but then also the tragic failures all mixed in together when we study that era.

<Dr.

Fields Black> I find this moment in time, the Civil War and the raid being an important moment in the evolution of what we call today, Gullah Geechie.

I also find that, you know, we're living in an interesting moment right now in a lot of ways with racial reckoning and social justice and some would say, the new lost cause, and I find the raid to be a really important prism through looking at what the Civil War meant to African-Americans and what we fought for and what we sacrificed.

>> Eventually, the federal government paid Harriet Tubman's Civil War pension in 2003, and in 2008, a bridge over the Combahee River was renamed the Harriet Tubman Bridge in memory of her contributions to the raid.

And recently, the U.S. Treasury announced that it would honor Harriet Tubman by adding her image to the $20 bill.

In addition, the National Park Service is creating a national park where she retired in Auburn, New York, in her honor.

Statues of Harriet Tubman have been erected across the country, and one is planned to go up in Beaufort County, South Carolina, where she served during the war.

<David> And I found it in there, there was a letter written by a gentleman down in Beaufort, South Carolina in Hilton Head.

I forget where he was exactly, but this gentleman was writing on behalf of General Hunter.

He wanted Hunter to stay in command rather than Quincy Gilmore, who would take command in June of 1863, but there's an interesting anecdote in there, where he described watching this major general commanding a department, David Hunter, pouring a pitcher of water into a glass and handing it to a Black woman like standing there like he was acting as one of his own, you know, staff members, basically, but he was waiting on Harriet Tubman, who he gave a glass of water to.

So it really, to me, gave a sense of the stature that Harriet Tubman had.

And Hunter was an abolitionist before the war.

So he was a big fan of hers.

He gave her a pass where she could travel on the, you know, the transports from place to place.

So, she was recognized for her military value.

Definitely by people, abolitionists, officers like Montgomery and Hunter.

♪ >> Among the great heroes and influential figures in American history.

Harriet Tubman should be recognized for being the real life super hero that she was, as well as being honored for her incredible contributions to our country.

If she isn't worthy, then who is?

Harriet Tubman died of pneumonia in 1913 when she was 91 years old.

♪ (Harriet re-enactor sings) Oh, freedom, my Lord.

Oh, freedom over me.

And before I'd be a slave.

I'd be buried in my grave.

And go home.

To my lord.

And be Free.

♪ music ♪ Thank you so much for watching.

And a special thank you to David Schafer and Dr. Edda Fields Black for not only the gift of their time, but for also sharing their incredible knowledge, and thank you to the talented artists who shared their paintings in this project, especially Sonja Griffin Evans, whose Gullah images helped bring Low country Gullah stories to life.

In addition, I'd like to send out a special and grateful thank you to the incredible talents of Cora Miller, a.k.a.

Hilton Head's very own Harriet Tubman, who always knows exactly how to bring her to life.

My name is Luana Graves Sellars and this has been a Low country Gullah Production.

♪ ♪

Support for PBS provided by:

SCETV Specials is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.