NatureScene

Fossil Butte National Monument (1993)

Season 4 Episode 6 | 26m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

Fossil Butte National Monument is located near Kemmerer, Wyoming.

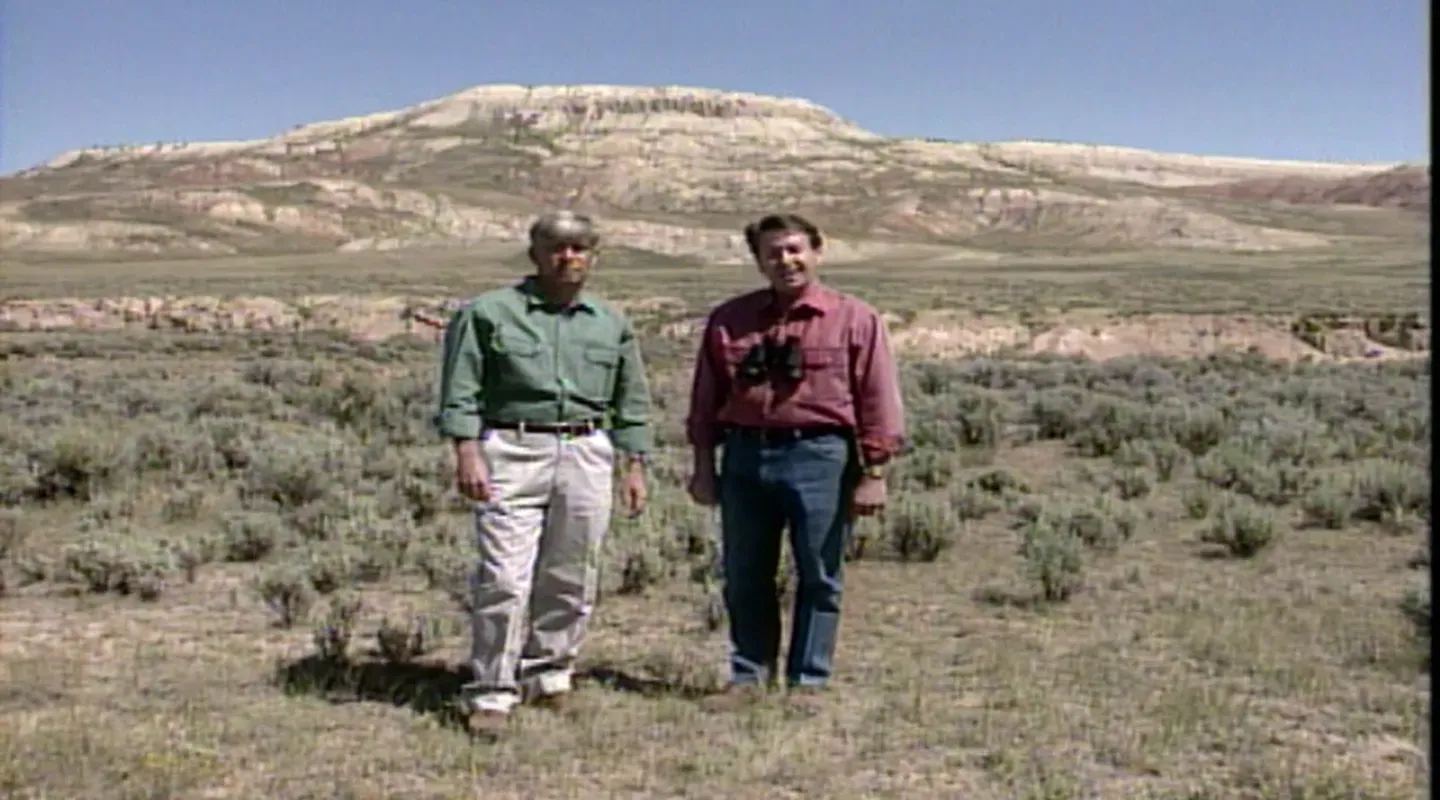

In this episode of NatureScene, SCETV host Jim Welch along with naturalist Rudy Mancke take us to Fossil Butte National Monument.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

NatureScene is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

NatureScene

Fossil Butte National Monument (1993)

Season 4 Episode 6 | 26m 45sVideo has Closed Captions

In this episode of NatureScene, SCETV host Jim Welch along with naturalist Rudy Mancke take us to Fossil Butte National Monument.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NatureScene

NatureScene is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipRudy Mancke: Wyoming's Fossil Butte National Monument allows us to take a close look at signs of life both past and present.

Next on Nature Scene.

A production of: Nature Scene is made possible in part by a generous grant from Santee Cooper where protection and improvement of our environment are equal in importance to providing electric energy.

Additional funding is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and by viewers like you members of the ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

♪ ♪ Hello, and welcome to Nature Scene in the semi-arid sagebrush country of southwestern Wyoming near the town of Kemmerer.

I'm Jim Welch with naturalist Rudy Mancke and we're at Fossil Butte National Monument.

A beautiful place here among the hills all around us.

This is going to be an interesting story, Jim because we're going to be able to go back in time a little bit and look at the fossil record here.

And, yet, we're also going to sample what's usually called inter-mountain grassland area of the southwest.

It's not really a true desert and yet, it's very, very dry.

Grasses usually dominate here but there are other plants I think we'll see that'll come in where there's a little extra water.

And, really, in this dry open area here when you look all around you ioioe domiqote plant is not the grasses but the big sagebrush and, really, not a true sage, as such but it has that interesting smell-- a turpentine-like smell-- when you bump into it.

And look at the leaves on that thing and three little teeth at the end of these leaves.

They have untoothed leaves that come on early in the year.

They're usually shed once it gets dry.

And then look at the early flowers coming in on that, uh, plant.

Small insect hanging on there in this light breeze.

Yeah, a little damselfly coming...

Uh, probably came from a wetter area and then flying out here to get used to flying and then to look for a meal.

They eat small insects.

Wings folded back.

Yeah.

A lot of animals use the sagebrush you know, as shade and also to find a meal there.

That is an interesting plant-- small leaves.

Interesting story there but a totally different story when you turn around because here are the remnants of the bottom of a large lake-- freshwater lake.

Two formations there that, uh, you can see fairly clearly.

The one that's sort of reddish in color is the wasatch formation, stream-fed material-- uh, delta-like situations that were deposited in a lake.

And then the best fossil fish-- some of the best in the world of eocene age-- is found in that green river formation which is the lighter material above it, Jim.

And I think that's going to be a very exciting story-- a trip back in time, so to speak-- as, uh, as we look at the past and the present here.

We're going to try to work our way back up there.

But there's so many interesting things here.

Again, I like that combination.

We'll start off, though, with a look back in time with some fossils.

♪ Rudy, that is quite a challenge-- coming up this trail, the quarry trail.

It's from 6,800 at the valley floor to over 7,400 feet up here where the quarries are.

It's a long walk but I think it's worthwhile to come to this area and see where that quarrying occurred.

Well, geologist Dr. John Evanson... Evans made the first discovery of the fossil fish in 1857.

But a lot of quarrying has been done since then.

And that, uh, lake, really, was here when the climate was much more lush than it is now.

A lot of palms were around it.

Very diverse hardwood forests in the mountains.

But that was then and this is now.

Climate has changed.

There's been a little uplift.

There's been a lot of erosion.

And you get those long views where the rock has been removed.

And there is that wasatch formation-- the red down there.

Really, what we want to look at, though is that green river formation which, really, is right behind us.

This was the level of one of those quarries.

You can see where they dug out and you can see fragments of that green river formation there.

Hopefully, we'll find some fossils as we walk up.

Well, the lake itself was 50 miles long and about 60 feet deep here at the center portion.

But we're talking, what?

50 million years ago.

Oh, yeah, we're talking eocene times.

We also arlking about fossils that aren't just fish fossils.

Here's a little bit of plant material.

Just look here at some of the material that's worked its way down and they're fossil fragments, anyway.

So some of the pieces that have uh, the darker in it could be fossiliferous?

Yeah, I think we can have a chance... Yeah, there are enough clues right here, just with what we've picked up to tell a pretty good story about the past in this part of Wyoming.

Very much like fish vertebra.

You can see where the bones were.

You can see the vertebral column the ribs, the fins.

The head's missing, now, on this one but, really, in fairly good shape.

Some of the best eocene fish fossils in the world have been found right here.

So you see that they were buried quickly.

Cause of death in large numbers-- we don't really know.

They are still great mysteries.

But isn't that neat?

Oh, yes, and you're saying there are tens of thousands of them in this formation.

Now, when there are a lot of fish you would expect... Look at this next one here.

This is really amazing.

What is that?

Right here, at the end of my thumb.

One of the coprolites, coprolites-- fish droppings that have become fossilized.

When you have a lot of fish skeletons you're going to expect to find many, many more of these fossilized droppings.

You can see it there in that material that little thin bit of material.

Going to the bottom a little harder than the material around it becoming mineralized and then fossilized.

That's kind of interesting to see that in place.

That has a shale look to it, the material around it.

Look at this, though.

Look at this next thing.

Now what is that?

Look along there.

Look at the blade of a plant.

See that?

Maybe one of the grasses, I don't know from here.

But that is beautiful.

A little bit of the vegetation.

That black color is carbonized material buried fairly quickly in that lake bottom.

Is this more, more plant material?

Oh, yeah.

Oh, oh, oh, even better.

Look how big it is and you see the way it's bent a little bit there.

Oh, that's nice.

And, again, carbonized, see?

Carbonized material, a great deal.

Now this one has actually, a fish head on it.

Oh, this is the best one.

This is the best one because we can see the face of the fish swimming around in that lake-- it was a big lake-- in that lake becoming saline.

And then, also, right there, toward the front... Can you see that coprolite that's been added?

Look at this.

Look at this.

Added, probably, over the dead body of the fish.

But, again, even better on this one you can see the ribs and the vertebral column.

We should leave these for other visitors to enjoy since everything is protected by the park service.

Oh, yeah, and that's the right way to do business.

And, really, I want to take a look at this layering right up ahead next.

♪ This place, now, gives us a really good opportunity to get a look at what used to be the floor of fossil lake-- uplifted now-- and gives you kind of a feeling as you get closer to it of that layering, Jim.

Different kinds of sediments here.

Look at it.

Some volcanic material.

Streams running into the lake were bringing debris from high ground around it and then as it was filling the lake slowly, but surely it trapped bodies of plants and animals and caused that fossilization to occur.

But it's neat when you put your hand up against something that's, you know, 55, 65 million years old-- eocene age-- that was once on the bottom of a lake and now frozen in, uh, in place.

Climate, uplift and erosion all...

Gave us this chance to look at it.

Yeah, this was one of three lakes that during eocene times were here.

It didn't last very long.

It was the deepest, but the smallest.

But it left the best fossil record-- especially fishes-- of any in the world.

And there's a marvelous interpretive center here that shows a better view of this than we get here.

And, yet, this is really where the action is.

Interesting place to see.

And the layering, again, uh...

The stratigraphy here is nice.

Sedimentary rock-- slowly, but surely forming-- that's where you go to look for fossils.

We're going to work our way down from here and then go back up another way and see how water affects this world.

Let's go there next.

♪ Well, this is the mile-and-a-half fossil lake trail-- one of the two trails on the monument-- and a beautiful late summer day.

And higher than where we started now, see, so we'll be seeing some changes.

I guess one of the things that really comes into open areas like this is that foxtail barley.

I mean, it is all over the place.

One of the grasses that does well here.

We said this was a grasslands/sagebrush area and this is a dominate grass.

Look at it nodding over like that.

Very well named because of the foxtail look.

Yeah, it does have that foxtail look.

Blown easily now-- the seed blown easily by the wind and spread all over the place here.

A few flowers around here.

Well, there are lots of flowers.

yeah, this is a great place to see a little bit of the variety of flowers.

But look up here.

Look at the sage grouse going right there.

We must have scared it up.

Oh, wow, that's a first for me.

Look, just the head's sticking up.

Female's heading up the hill and this is perfect habitat for that, now.

Oh, that's neat.

Scared it up just by our movement, I suppose.

Possibly the hen of the sage grouse?

yeah.

Yeah.

In the winter, now theyally depend on that sage for food but they feed on a lot of other things this time of year.

A lot of plants down here.

Just look right in front of us.

Uh, asters all over the place.

That fall aster is very, very common here.

One of the composites...

Uh, great variety of composites we.

Uh, ray flowers and disk flowers crammed together.

That's pretty.

Really nice and there's been a little extra rain so the flowers have lasted a little bit longer than normal.

Rudy, is this one of the docks over here?

Yeah, that is one of the docks.

um, I'm not sure which species it is.

Genus name would be rumex but that's the fruit on it.

You see kind of a pinkish look now and it'll get a darker brown.

Often you see that plant used in dried arrangements and the leaves are edible on that species.

Native americans took advantage of a lot of these species.

Now, look over here at the, uh... One of the geraniums.

Very showy.

About a one inch flower.

Wow, isn't that beautiful?

Yeah.

With those purplish lines on the... On the petals there.

I think that is richardson's geranium.

But not only do you have the nice flowers showing but look at the fruit-- you can see why many of those geraniums are called cranesbills because the fruit does resemble the bill of a crane.

Now, here's one you would expect to be associated with sagebrush and sagebrush is still here.

Rabbitbrush is the common name for it.

See the yellow?

That's another one of those composites.

Piles of flowers crammed together in one head.

And that offers, of course a tremendous amount of nectar to insects and look at the, uh, varied blue is the common name for that little butterfly that's sitting there.

Another name, though, is the blue copper.

It, in fact, is a copper, but it's bluish in color.

And look at the spread wings-- oh, that's nice.

Well, in field guides, blues and coppers are so often linked together.

They're very closely related and, uh... That one is really sunning right there.

And all around us, Rudy, some taller grass is sticking up above the foxtail barley what kind are those?

Basin wild rye is the common name for that and you're right it does get really tall, and clumps.

You see again it's clumped.

Great variety of grasses here and a lot of animals take advantage of those opportunities of course.

Nice breeze this late summer day.

Yeah, this is a beautiful time to be here and especially when there's been a little extra moisture this is one of the little seepage areas that the bridge goes over.

Seep-spring monkey flower; absolutely glorious.

Look at the color there.

Beautiful yellow-- perfect name I suppose.

A little bit of orange in the throat of the flower, yeah.

Monkey flowers in this part of the United States are very diverse but they need a little extra moisture and these little seepage areas are absolutely perfect for that plant and I'm sure quite a few others.

There's another interesting plant right there.

Snowberry is the common name for it and this is the perfect time of year to see why.

Look at the fruit, it's snowy white.

Yeah.

The fruit is a snow color and small leaves... A little shrubby plant that's very, very common in this part of the United States.

And look... Down here below us.

We've come up.

Now, we're looking back down.

Look at the pronghorn.

They came right through there.

They can come out of a draw so quick and there they are.

That's a beautiful animal, isn't it?

So typical of this part of the United States.

Only known from North America.

One of those animals... Look at the male there with those large horns.

Both sexes have those horns and there's a bony inner core but the outer horn is shed every year.

And, of course, that one prong sticking forward gives it the name pronghorn.

Very typical of this part of the United States and they're down there in the sagebrush just, uh, browsing on this, that and the other.

I often see them at a distance and they could be about 3½ feet long 'cause it is a larger mammal.

Yes, massive animals...

Sometimes really white rump.

You can see the white rump on it.

And white bars... You can see the female, the younger one coming toward us there a little bit.

Curious...

Giving us a good look.

You don't see the horns very well-developed on that yet but you see the two white bands on the front that are typical and then that white rump patch that you see every now and then.

And that can serve as warning when they're frightened.

Althose bristles can come out.

Fast-moving animal.

I mean, that's the fastest animal that we've got in North America.

Can really bolt away but they're taking it easy really.

This seep runs on down there and gives them a little extra moisture.

And that's why they're coming this way and, boy, that one is really curious...

Looking right in our direction.

Pronghorn antelope can reach 60 miles an hour if pushed.

Leap 20 feet.

Great animal.

Those are amazing animals.

Beautiful things all around us.

Here's some more flowers to take a look at.

And these jump out at you really.

Scarlet red on that paintbrush.

I think that's a really good common name for that plant.

Beautiful flower and it is a state flower of Wyoming...

The indian paintbrush is.

It's one that's kind of interesting because it's often parasitic on other plants that it's, uh, growing around and there it is right there by the, uh, sagebrush so it might be parasitic on that.

But red tips there looks like, you know a paintbrush that's got a little bit of red paint still on it.

There's another red one closer that looks quite different.

Scarlet Gilia is the common name for that.

Trumpet-shaped flower and that corolla tube, you know spreads at the end and flares back.

Bright red... Little bit of white on the flared part of those trumpets.

But that's a typical species here also.

Blues, greens, yellows...

Bright yellow.

Look at that bright yellow.

Another one of those composites that we were talking about a moment ago.

Gumweed is one of the names for it.

Really, if you feel the base of the flowers it's sticky like gum to the fingers.

But again that provides lots of flowers which means lots of nectar.

Look at the fritillary that's come to get a quick sip.

A beautiful butterfly... Just out.

I mean, there's not a scale missing on those wings.

Gosh, that's beautiful.

And then, look right over here.

Look right over here.

Top of that branch.

That's, uh... That's a large bird.

That is a flicker, Northern Flicker.

In the old days that would have been called a red-shafted flicker variety but now they're lumped together.

That is, we don't see the red much.

And Rudy, that is a woodpecker?

Oh, yeah, and it's a female.

Gray on the head there, good beak and then that black-- almost like a bib-- on the front.

It's typical of the flicker.

And, really, I think that animal is aiming in the right direction because this extra moisture now has caused a perfect habitat for some broadleaf trees look at the quaking aspen, trembling aspen all ahead of us.

And I'm sure that woodpecker finds meals in those trees.

Let's head in that direction next.

♪ Those aspens really dominate here now.

With this extra moisture a broad-leafed tree can actually survive here.

But it takes moisture.

One of the first trees in to an area that's been disturbed.

And you see they come up from the roots, don't they?

And they're about the same sizes which is a special technique of the aspens.

Well, they come up from those underground roots and pop up and basically a whole cluster of trees might actually be the same genetically.

So, if you were to cut them up they would be clones.

The same plant.

So they do have seed but in the main they come up from root systems.

Yes... Vegetative and sexual reproduction.

Look at what the beavers have done here now.

This is amazing.

I'm always amazed at the way beavers rearrange the world to suit them and you can see the work going.

Seepage area's all you've got.

Very little flow of water.

And yet, with a dam properly placed you back it up, create standing water which is a totally different habitat remember those little damselflies that we saw earlier would need to come to standing water like this in order to reproduce because they lay eggs in water.

And this is such a nice little area-- unique, really-- area because there's not a lot of standing water in this part of the united states.

Beavers will kill these aspen off and move on to another grove.

Yeah, take the aspen bark change it into beaver and then use the wood itself to build dams like this.

And you can see the work here.

I mean, this is...

This is beautiful work.

And recent.

Like last night.

Oh, yeah.

Well, look at all the mud, now.

Blobs of mud that's put into place and then all of the sticks.

Many of those sticks, bark stripped off, now.

The beavers ate that.

Changed it into beaver and then used the wood.

And you can see cut trees all along.

There's the lodge over there in the distance.

Workin?ñin this little valley and changing the world.

Rearranging things.

That's the way nature works anyway.

One dragon.

You see him?

I see him down there.

I see him.

Saw him at the same time you did.

Kind of a yellowish look.

Looking right at us.

And that one is one of the meadowflies is the common name for it.

Sympetrum is the genus name.

Wings down, looks fairly fresh.

And again, a perfect place, now, for them because they also lay eggs in water like the damselflies.

And then find food-- insects-- all around the edges of this standing water.

Beaver dam's about the 7,200-foot level.

And, Rudy, we're going to work our way, I guess up toward those different trees on top-- one of the conifers.

Well, the water runs out.

When it gets to drier situations up there.

I think the world will change.

Let's go take a look at that next.

♪ Little windier up on this ridge.

Here's that pine we were looking at.

There's several up here.

Yeah, limber pine seems to do well in these dry, exposed sites.

Boy, it really is exposed here, isn't it?

It is.

What a valley and what a view!

Oh, my goodness.

What a beautiful view.

With the outcrops of rock, now, that we've seen earlier still there in the distance.

The wind, you know, has an effect on the plants and, to some degree, the animals that are living here.

But there are wonderful views here.

Not a lot of vegetation to block the geology.

Way off in the distance, those beautiful mountains.

Much higher than we are right here.

Wasatch mountains there, over in Utah.

So we're right on the southwestern corner of the state of Wyoming.

Isn't this spectacular?

Little animal over here.

He's got quite a place for a house and a view.

( Rudy laughs ) golden-mantled ground squirrel is the common name for that.

Do you see the golden brown on the face and on the shoulders?

No stripes on the face at all.

And then that striping on the back that is very, very obvious.

But just flat down now.

Warming up a little bit because I guess the trunk of that tree is warm and enjoying the beauty of this day.

This winter will be really hard on him.

But he'll hibernate, I guess.

Very, very common animal in this part of the United States.

Of course, this area is covered with snow and the wind does blow some of the snow off in wintertime.

Yeah, and it exposes things like this to animals that are looking for a meal.

They hang on.

Two shrubby species here that really do dominate.

One of them has got, really, a couple of names.

Antelope brush is one name.

Even though the pronghorn which sometimes, you know, are called antelope don't feed on it much.

But bitterbrush is a better name.

The foliage and the fruit is bitter but animals love it.

Mule deer especially love to browse on this.

And the golden mantle ground squirrel might come up and get a little bit of fruit.

I see some fruit on it there.

The larger leaf plant.

What is it?

The larger leaf plant-- with fruit on it, too, now-- look at the fruit there-- is serviceberry.

Sometimes people call it sarvis.

That's another common name for it.

It's in the rose family.

The fruit is edible.

Humans feed on it.

And quite a few other animals take advantage of that opportunity.

But you see two shrubs here that are really very common.

Low to the ground, though.

They normally grow a little bit higher, but not right here.

This limber pine has seen better days.

Oh, yeah.

Oh, my goodness.

Strange little tree, isn't it?

It is.

See if you can get one of those cones down there.

I'm going to reach up and grab...

Pop off one of these little clusters of needles and see what makes this limber pine.

Less than five needles to the bundle.

Yeah, this is very, very helpful in identifying pine trees.

How many needles a bundle?

And this one does have five with a little bit of a curve on them and that's typical of limber pine.

Sometimes people call this rocky mountain white pine because, again, white pines also have five needles in a bundle.

The other thing that you use to identify this tree, though, is the cones.

Female cones.

And you see them there in your hand.

The size of them.

Very thick, kind of scooped-out scales on that cone.

The seed are large, and that provides food for lots and lots of animals up here, too.

But limber pine, the common species on this ridge.

Course, the name limber pine comes because they have to be limber in the breezes like this and they bend very easily.

You can take a few branches bend them all the way back and they don't even split.

Although this tree is in trouble.

Look why.

Look at the base.

Something's eaten at it.

Porcupine working on this tree, getting the bark-- inside bark of the tree and feeding on it-- like the beaver was doing the work down... Near the water on the aspens.

Here's the porcupine a relative of the beaver, working here.

I can see a little bit of gnaw marks all up and down the side of that tree.

Again, one of those interesting connections here.

8,200 acre in the monument and views, glorious views in every direction.

Yeah, and look back down where we were a little bit earlier.

You can see where those little streams-- little seep areas-- run along down because there is the quaking aspen.

Boy, that would be beautiful in the fall.

Lots of beautiful views.

Let's keep going.

♪ This is the highest point we'll be able to get to and another magnificent view.

Millions of tourists go into northern Wyoming for the mountain scenery but here in southwestern Wyoming it's absolutely beautiful.

Oh, yeah.

Great.

And, really, the geology is so nice with the green river formation the layers right in front of us poking out all the way around here.

And then that beautiful view of Fossil Butte in the distance.

Flat top and erosion along the sides.

And the reds of the wasatch and then the beautiful green quaking aspen below us.

It's an exciting place and summertime is the time to come here.

Today's visitors can see the wildflowers and the animals as well as the record of what took place.

I think that's a nice combination, too.

You can take a trip back in time with a little detective story using the fossils and the rocks here.

And then, of course, the plants and animals that are here today are interesting great variety of habitats and the park service makes all of it very accessible.

Come and see it for yourself.

Fossil Butte National Monument in southwestern Wyoming near the town of Kemmerer.

Thanks for watching and join us again on the next Nature Scene.

♪ ♪ Nature Scene is made possible in part by a generous grant from Santee Cooper where protection and improvement of our environment are equal in importance to providing electric energy.

Additional funding is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and by viewers like you members of the ETV Endowment of South Carolina.

Support for PBS provided by:

NatureScene is a local public television program presented by SCETV

Support for this program is provided by The ETV Endowment of South Carolina.